Acid Bath Murder

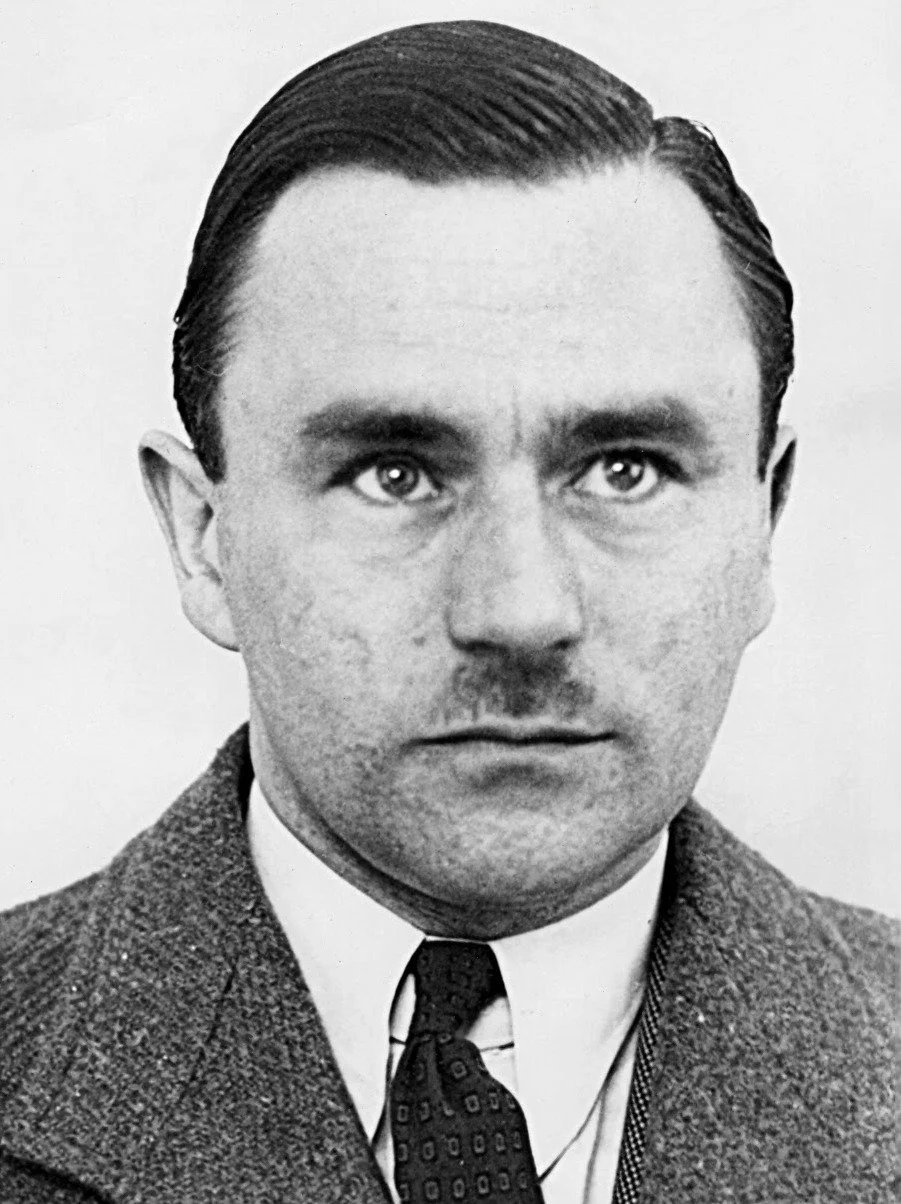

In the aftermath of WW2, Britain found itself confronting a new breed of criminal; educated, methodical and dangerously confident in the limitations of forensic science. Few embodied this more than John George Haigh, the Acid Bath Murderer. Between 1944-1949, Haigh murdered at least 6 people, dissolving their bodies in sulphuric acid and believing that he had discovered the perfect crime. His guiding principle was simple and, he thought, unassailable, No Body. No Murder.

Haigh's crimes and his conviction stand as a pivotal moment in the evolution of modern policing. They simultaneously exposed vulnerabilities of mid-20th century forensic science and the growing determination of detectives to adapt, innovate and challenge criminal assumptions. Nowhere is this story is more relevant than Sussex. Where Haigh’s crime spree finally unravelled.

A criminal shaped by confidence.

Born in Lincolnshire in 1909 to a religious fundamentalist family, Haigh was intelligent, articulate and deeply manipulative. He presented himself as a successful businessman, gaining the trust of his victims before killing them for financial gain. Unlike most violent offenders, Haigh was not impulsive. He planned meticulously, rented workshops, acquired industrial quantities of acid and researched chemistry extensively.

By the mid 1940's, Haigh became convinced that murder prosecutions depended almost entirely on the recovery of a body. Without remains he believed that the police would be unable to prove that a crime occurred at all. This was not a fully irrational belief as forensic science was very much still in its infancy. Corpus delicti (proof that death had occurred) remained central to all murder investigations.

The Acid Bath Murders

Haigh's method of murder was as gruesome as it was calculated. He typically killed his victims by gunshot or blunt force, he would then dismember the bodies and dissolve them in sulphuric acid inside large containers. The remains were typically poured down the drains or disposed of as waste. He often retained personal possessions and documents, using them to forge letters and continue financial fraud long after his victims were dead.

It was in Crawley in 1949, that Haigh's foolproof method hit an obstacle. After murdering Olive Durand-Deacon, a wealthy widow, Haigh attempted to continue accessing her finances. However, his behaviour attracted attention, and police began to scrutinise the inconsistencies of his story. Crucially, investigators were no longer accepting the absence of a body as proof of innocence.

Police turning the tables.

By the late 1940's, British policing was becoming more investigative, more collaborative and increasingly willing to use circumstantial and scientific evidence. In Haigh's case, Sussex and Metropolitan Police detectives worked together to reconstruct events through witness testimony, financial records and physical traces.

When the police searched Haigh's workshop in Crawley, they found containers of acid sludge. What Haigh assumed to be meaningless residue became the key to disproving his explanations. Forensic scientists were able identify human remains, including gallstones and fragments of bone that had survived the acid dissolution. These findings demonstrated that a body had existed, even if it had been deliberately destroyed.

Haigh was reportedly stunned. His courtroom demeanour revealed a man whose intellectual confidence had collapsed. His ‘perfect crime’ had been comprehensively uncovered by a combination of patient detective work and advancing forensic science.

The trial and its legacy

Haigh's trial in Lewes in 1949 drew national attention. He attempted to argue insanity, claiming that he drank his victim's blood. The court rejected this defence. The forensic evidence, although limited by modern standards, was compelling enough to establish murders beyond reasonable doubt. Furthermore, the evidence of financial fraud and a clear motive was enough to prove that he was lucid when he committed the murders.

Haigh was convicted of murder and executed at Wandsworth Prison later that year. This case marked an important shift in policing whereby cumulative evidence, forensic residues and logical reconstruction could be used to render a guilty verdict. Haigh's crimes forced police to rethink investigative assumptions and accelerated the acceptance of scientific expertise in criminal case.

Sussex, Policing, and the Modern Investigator

The Haigh case resonates strongly with Sussex policing history. It reflects a period when local forces were transitioning from traditional methods to more modern, evidence-led approaches. Officers were no longer simply responding to crimes; they were reconstructing them.

Today, visitors to the Old Police Cells Museum in Brighton encounter a very different policing world; DNA profiling, digital forensics, and national databases. Yet Haigh’s story reminds us that progress was hard-won, often driven by criminals who believed themselves cleverer than the law.

Haigh was wrong. His murders did not expose a flaw in justice, but rather forced policing to evolve. His case stands as a grim but important reminder: the absence of a body does not erase a crime, and criminal certainty often collapses under careful investigation.

In confronting Haigh’s chilling theory, mid-twentieth-century policing proved something enduring: that truth, persistence, and adaptation remain stronger than even the most calculated attempts to defeat justice.